PIPEDREAM is the seventh known malware affecting industrial control systems (ICS). It’s a flexible ICS attack framework and the first cross-industry scalable ICS malware that could be used for disruptive or destructive effects. Since the public release of information in April 2022, Dragos has been running PIPEDREAM malware against devices (i.e., runtime testing) to clarify what the toolset can do. This blog post is a summary of the runtime results. Dragos Principal Malware Analyst Jimmy Wylie presented this information at DEFCON30 in detail on August 13, 2022, available on DEFCON’s YouTube channel and embedded below. We also recommend that you read our previous blog discussing the PIPEDREAM malware for details on each component, as we won’t be covering that here.

Analyzing PIPEDREAM – Challenges in Testing an ICS Attack Toolkit

Key Takeaways

- We’ve confirmed that EVILSCHOLAR can target CODESYSv3 devices. Schneider Electric controllers are likely only the initial target.

- BADOMEN can manipulate the 1S-Series of Servo Drives, not just the specific R88D-1SN10F-ECT Servo Drive.

- BADOMEN cannot manipulate Omron Safety Controllers, but this is likely the next step in its development.

- EVILSCHOLAR and BADOMEN can achieve logic corruption and manipulation on target PLCs for disruption and destructive effects.

- None of our mitigation guidance has changed. Please see our previous whitepaper for that guidance.

Analysis Approach

PIPEDREAM was an interesting case in that we had to analyze five malware samples in parallel, which were essentially targeting four different “architectures”: Omron NX/NJ series controllers, CODESYSv3 Controllers, Open Platform Communications United Architecture (OPC UA) devices, and Windows OS. Here is the process we decided to follow.

First, we focused on static analysis of the malware (think: reading the code) while we acquired the hardware. This first static analysis pass provided us enough information to release conservative mitigation advice for the malware. Once that process was finished, we began the runtime analysis with PCAP collection. During runtime analysis, we tested which techniques work on which devices and tested any hypotheses from the static analysis process.

Once runtime analysis was complete, we released updated details and specific mitigation advice. Then if priorities allowed, we did some follow-up research like further firmware analysis.

So, where are we now in this analysis process? We’re just about finished with runtime testing for all the various components and are beginning to release the results publicly and privately to customers, starting with this blog.

Lab Testing Results

MOUSEHOLE

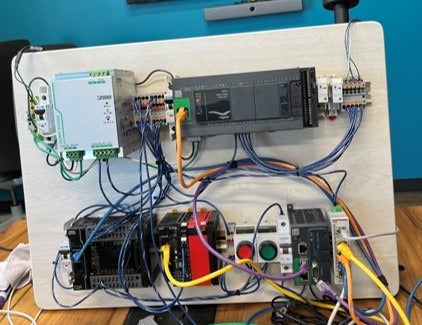

MOUSEHOLE was the most straightforward to test due to its reliance on an open source Open Platform Communications United Architecture (OPC UA) library. We tested it on a Kepware OPC server connected to Rockwell PLCs, controlling a mock water pipeline process.

After verifying that the malware could indeed interact with the OPC server correctly, we set about creating an automated attack, as that would likely be a more real-world attack scenario. In other words, we suspect that the attacker would use MOUSEHOLE to recon the target OPC UA-controlled process, remove MOUSEHOLE from the network, and then deploy an automated version of MOUSEHOLE for disruption.

Our experiment on our pipeline was successful. We could automatically log in to the server, change the maximum safe pounds per square inch (PSI) level (15 PSI → 100 PSI), set the pump speed to maximum, and close the solenoid valve. The PSI quickly moved beyond what was considered safe, and the pump began deadheading.

View the video of the testing results in the DEF CON presentation above – MOUSEHOLE Operator View, time stamp: 8:25; MOUSEHOLE Safe Shutdown, time stamp: 9:31; and, MOUSEHOLE Unsafe Conditions, time stamp: 11:43.

EVILSCHOLAR

Unlike MOUSEHOLE, EVILSCHOLAR was more difficult to test in the beginning. EVILSCHOLAR contains a custom CODESYSv3 implementation. That implementation, plus the built-in weirdness of standard CODESYS, presented some issues for us when trying to figure out which errors were lab configuration errors versus potential EVILSCHOLAR problems.

At first, we thought maybe it was a firmware versioning issue, but that turned out to be a mistake. Instead, we discovered that multiple parts of EVILSCHOLAR’s CODESYS implementation were broken due to a few invalid assumptions by the adversary developer. We could connect to the TM241 and TM251 with no issues if the devices were on a network of the correct size. We spent a couple of weeks making adjustments to the code and were then able to connect to the TM241, TM251, Raspberry PI, and Hitachi EHV+.

While we tested all the plugins in EVILSCHOLAR, we’ll only focus on testing its logic corruption potential. EVILSCHOLAR allows an operator to transfer files to and from the device using CODESYSv3. The process to test this is reasonably straightforward: pull the logic, disassemble it, modify it, and then transfer it back. This experiment was also a success.

We could crash and manipulate logic on the TM251 controller, creating various error and output states. In both cases, communications to the controller from the engineering workstation (EWS) are disabled unless you power cycle the device.

Unfortunately, we can’t share much more about this as we are still working through the responsible disclosure process. We reported the applicable vulnerabilities to Schneider Electric and CODESYS Group on June 22, 2022.

The fact that some of EVILSCHOLAR’s code is broken doesn’t make the threat any less severe. The CHERNOVITE threat group is likely investing plenty of time and money into developing EVILSCHOLAR. If we were able to fix it in a couple of weeks, it’s only a matter of time before the adversary overcomes the issues.

BADOMEN

BADOMEN provides similar abilities to EVILSCHOLAR but targets Omron’s NX/NJ series controllers. Its command line console leverages CVE-2022-34151, a hard-coded credentials vulnerability, to interact with an HTTP Server on the controller. The server has various common gateway interface (CGI) endpoints that both SYSMAC studio and BADOMEN use to manipulate and administer devices. In particular, BADOMEN leverages the “cpu.fcgi” and “ecat.fcgi” endpoints.

We’ve tested almost all of BADOMEN’s plugins, but for this blog, we’ll focus on the malware’s logic corruption and manipulation potential. Using BADOMEN’s backup and transfer modules, we crashed an NX1P2 controller by modifying the entry point function of the compiled logic to branch to a bad address. The crash prevents the EWS from doing a Program Upload and enabling Program Mode on the controller.

To recover, we tried to restore the controller via a secure digital memory card (SD) card which failed, but this did, for unknown reasons, let us put the device in Program Mode. This then allowed us to factory reset the controller and restore the logic.

BADOMEN – Servo Testing

BADOMEN contains a module to target Omron Servo Drives and their parameters via EtherCat. A Servo Motor spins a shaft. A Servo Drive powers the motor, controls the motor and handles communications back to the governing programmable logic controller (PLC). Servos can be found in pipelines opening pressure control valves to regulate the flow of gas from point to point. They can also be found in electrical switch yards where they are used to put vacuum breakers in an energized position.

These parameters are essentially configuration values. For example, there are parameters for controlling the direction of rotation of the motor as well as detecting excessive speed. Initially, the malware appeared to target the R88D-1SN10F-ECT Servo Drive. We confirmed that the malware can manipulate parameters on this drive. The documentation showed that all drives in the 1S series shared the same functions and parameters. Thus, we purchased a smaller drive, the R88D-1SN01L-ECT, and its compatible 120VAC motor, R88M-1M10030S-S2. We were also able to communicate with that drive using BADOMEN. This result means that the servo module very likely affects all drives in Omron’s 1S series servo drives.

BADOMEN – Logic Manipulation

The Logic Corruption test proved that we could modify the running logic and get it to execute on the device. This meant that we should be able to make more meaningful changes to the logic to manipulate a process. Further, we wanted to change the servo motor speed, and the only way to make that happen was to modify the appropriate ladder logic function arguments. Thus, it was natural to test logic manipulation using the servo motor. (Also, it’s more fun to try this manipulation with a moving device and get visual feedback versus simply setting outputs.)

We started with creating a ladder logic program to spin the motor. Then, we disassembled the compiled ladder logic to identify the call to MC_MoveRelative. Next, we modified the Velocity argument from 40 degrees per second to 18000 degrees per second, the maximum motor speed.

View the video of the testing results in the DEF CON presentation above – BADOMEN Max Velocity, time stamp: 28:09.

BADOMEN – Safety Controller Testing

One of the more worrisome aspects of BADOMEN’s targeting of NX/NJ series Omron controllers is that they are also used to communicate with an Omron safety controller, SL3300. That means that BADOMEN might have the potential to manipulate a safety controller, similar to the TRISIS attack.

From the beginning, when configuring the SL3300, it was clear from the UI that safety programming was a different process. In particular, transferring logic required separate DEBUG modes and Safety validation. We saw no references to these modes in the BADOMEN malware. Capturing a packet capture (PCAP) clarified the issue.

We realized that transferring safety logic occurs over a new CGI endpoint, “nxbus.fcgi,” with a different function (and probably protocol) than we had seen before. BADOMEN does not support this endpoint.

While this is good news, for now, building support for this endpoint is a likely next step in development for BADOMEN, as safety controllers are a common part of ICS processes. Take the previous servo attack as an example. In the real world, a safety system would monitor the servo for over spinning and excessive vibration. So, conducting that kind of attack in an actual process would require disabling or changing the logic on the corresponding safety controller.

In Conclusion

PIPEDREAM is an existential threat to the ICS community. This toolset is likely being actively developed and financed. It is already capable of disruption across industries, including CRASHOVERRIDE-style disruption, pipeline disruption, and servo manipulation. We’ve confirmed that PIPEDREAM, with little development effort, can target devices speaking the ubiquitous CODESYSv3 and OPC UA protocols. It can manipulate servos in the 1S-Series of Omron Servo drives. While it cannot target Omron Safety Controllers, this is undoubtedly the next step in its development. We’ve confirmed that the toolkit can achieve logic corruption and manipulation on CODESYSv3 and Omron devices.

Essentially, our runtime testing has confirmed the results of our initial analysis and, if anything, proves that this toolset is more threatening than we initially thought. However, it appears that the mitigation guidance we released in April 2022 still applies, and we recommend that site owners and operators implement these mitigations where applicable.

Ready to put your insights into action?

Take the next steps and contact our team today.