The term “cyber risk” is a universally unloved term.

For many of us, the phrase invokes memories of continuous security assessments, meaningless heat maps, and constantly telling people “we’re not IT, we don’t do that.” It’s political battles between IT and OT, budget wars, and oversimplifying years of work into maybe two PowerPoint slides.

There is a reason why, as practitioners, we’re constantly in the cross hairs when it comes to cyber risk and cyber program management—because, compared to other operational areas, we are, without a doubt, the least mature in communicating and documenting risk. That’s not a criticism, but an observation. When compared to financial risk, which can provide quarterly estimates in real dollars of associated impacts, or safety risk, which leverages real incident data to estimate potential health and human safety concerns, or even disaster recovery, which can help model natural disasters and their frequency—cyber risk is still articulated in traditional reds, yellows, and greens. As a matter of fact, according to Microsoft and Marsh, 43% of organizations use qualitative “traffic lights” to report on cyber risk, compared to only 30% that quantify it similar to other areas of business risk. When executives compare the discussion of various risks across the corporation, it feels like we’re bringing crayons to a math test.

And executives are increasingly frustrated with the lack of visibility into this growing risk. Each of the previous risks discussed—finance, safety, and natural disasters—focus on business impacts, usually inclusive of operational downtime, liabilities, or financial impacts. Most cyber risk assessments, however, focus on vulnerabilities and technology gaps. Before we even get started, we’re speaking a different language. It is no wonder why, in a recent survey by Deloitte, only 38% of CEOs and 23% of board members are “highly engaged” in their organization’s cyber risk discussions. As much as practitioners don’t love “cyber risk,” neither do their executives.

The benefits of a mature cyber risk discussion, however, far outweigh the pain points. Organizations that have been successful in engaging their leadership are able to sustain their programs, unlock additional budget, and grow their team.

So how do we, as ICS security leaders, successfully understand, manage, and communicate cyber risk concerns?

A New Focus

In our new guidance issued this week, Dragos outlines an approach to help industrial leaders create new (or refine existing) cyber risk management processes.

This process is not intended to reinvent the wheel, but rather augments existing risk management practices to include relevant discussions for industrial control systems and OT environments. Based on a collection of industry resources and standards, the guidance is meant to help executives, risk managers, and practitioners speak the same language when it comes to industrial cyber risk.

Why?

Simple. As noted in the 2020 Year in Review, our team has identified an increase in cyber threats and ICS-specific vulnerabilities—yet our global professional services still observe a lack of basic security controls. These include identification of crown jewels, proper segmentation, and visibility in OT networks. This disconnect is not due to an unwillingness to secure vital systems, but it is more likely attached to difficulties in measuring and communicating cyber risk concerns across organizational boundaries. As threats and vulnerabilities continue to rise, so does our overall risk as industrial organizations. Our security programs, logically, must mature to address those risks.

A More Complete Picture

If an industrial organization spends more on securing their website than their process control network, that is usually a dead giveaway that cyber risk is ill-defined internally. The root cause can be traced to a few key issues:

- IT-focused standards have historically “claimed” cyber risk compared to OT standards and frameworks. IT security teams may therefore own the cyber risk conversation, but have not engaged OT teams.

- The broader organization is unaware, or unable to articulate, OT cyber risk.

- The OT security program is based on a hero or team of heroes with very little documentation or visibility outside of their business unit. This leads to a lack of communication of security needs to address risks.

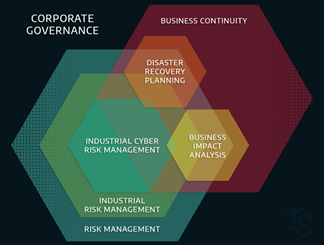

Regardless of the starting point, each of these problems can be eliminated by structuring a cross-cutting set of tools and techniques to analyze and manage cyber risk in industrial environments. The great thing is, many of these tools already exist across organizational boundaries. Our actionable guidance includes identifying skills, such as business continuity and disaster recovery, that can complement industrial cyber risk program management. As a matter of fact, we aim to help organizations understand that industrial cyber risk is just one component of dependent programs that include feedback across Process Hazard Analysis (PHA), Business Impact Analysis (BIA), Disaster Recovery Plans (DRP), and other interlocking studies related to reliability, safety, and process impacts.

Mastering industrial cyber risk means understanding how these programs not only relate to one another, but compliment the business objectives to deliver product or critical services to customers. Even within “industrial risk management,” which includes safety and reliability, there are critical overlaps to cyber risk—especially when understanding how assets are used in operations and subsequently protected.

OT-Specific Guidance

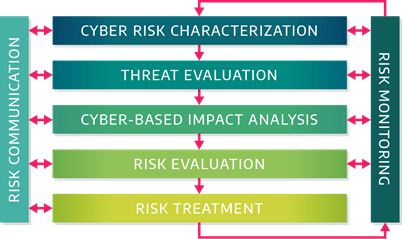

While the Dragos process builds on existing standards and frameworks, it also points out the uniqueness of OT networks and industrial control systems. For example, how should asset owners and operators account for resilience or manual processes when the control system is attacked? No IT-centric guidance will account for physics. Or impacts associated with national security from critical infrastructure outages. Our process builds on well-established best practices, but allows users to tailor it to their specific risks and concerns. We also understand that some organizations will already be using a risk management program. Perhaps it’s IT-focused, like ISO 27000 series. Or maybe it’s more generic than that, with legal and financial risks identified through ISO 31000. Maybe there is no standard at all, but there’s an ad hoc process in place from a risk leader. No matter your background in cyber risk, this process can help augment existing practices with a familiar, yet OT-specific, framework. At a high level, the process can be broken down as follows:

Where each of the components can be described through the following:

- Cyber Risk Characterization is a preparatory step that ensures all the relevant information to “frame the risks” are present, including inventories, system architecture, safety analysis, disaster recovery plans and any previous risk assessments.

- Threat Evaluation builds specific threat profiles (the document leverages an example of one for XENOTIME using MITRE ATT&CK for ICS terminology where possible). Threat profiles are introduced as a tool for understanding the threat environment as an input into industrial cyber risk.

- Cyber-Based Impact Analysis customizes “impact criteria” to produce objective thresholds for “high” or “low” impacts, based on the uniqueness of the industrial organization—including possible impacts to national security. Based on impacts and threats, most organizations will be able to build an effective risk management program, regardless of their maturity. A lightweight maturity model is introduced to let organizations rank themselves prior to implementing the process.

- Risk Evaluation uses an additional workflow on the best way to perform a cyber risk evaluation for industrial controls systems and includes:

- Architecture Reviews for systems that require basics security controls and considerations

- Qualitative Risk Evaluations based on risk scenarios to identify high and very high risks

- Quantitative Risk Analysis applied to high and very high risks where additional technical rigor is required.

- Risk Treatment takes prioritized risks, after they are evaluated, and manages them with a variety of technical, procedural, and financial controls. We provide examples for avoiding, accepting, deferring, controlling, and transferring industrial cyber risk. For example, investing in preventative controls, such as traditional perimeter defenses, could be a treatment response for an identified cyber risk. However, other options could include increased OT network visibility, or even using engineering (or passive safety controls) to lower the potential impacts.

- Risk Monitoring, which occurs throughout the previous workflow, introduces the use of a risk register as a repository of the identified risks, their prioritization, and the status of the risk. Industrial cyber risks requiring monitoring across multiple categories of impact, including potential environmental, safety, and even national security impacts—all of which need to be tracked based on their severity.

- Risk Communication highlights the use of risk taxonomies—a common lexicon for discussing risks—is based on MITRE ATT&CK for ICS and other more generic risk dictionaries. The guideline also includes discussions for executive reports and metrics for managers and boards that highlight OT-specific concerns, like potential reliability issues or system downtime.

Anyone familiar with the ISO risk management standards should feel right at home leveraging the document. And, similarly, a reader with no experience in risk management should be able to adapt their processes using this guidance to mature and improve their discussions of OT-specific cyber risks across their organization.

Mastering Industrial Cyber Risk

Industrial cyber risk does not need to be painful. It can not only be managed, but it can be mastered.

That does not mean the risk will ever be “zero” (we do not ever assume safety risk is zero, so why would we hold the same standard for security?).

Instead, we can master it by understanding our resiliency, threats to our control processes, vulnerabilities in our equipment, and impacts associated with cyber incidents. We can allocate resources to decrease our overall risk. And we can present all of this data to an educated board and executive suite using metrics that make sense to them.

The end result is a mature risk management program, similar to what a CFO would use for financial risks, but for security. And we should strive for that level of understanding from our risk leaders; it only makes our industry better.

Cyber risks, after all, impact every aspect of our industrial organizations. Cyber risk can impact the safety, reliability, and finances across each business unit. So if we are not managing cyber risk to the level of these other risks… are those risks truly being managed?

Ready to put your insights into action?

Take the next steps and contact our team today.