On May 7th, public reporting emerged about Colonial Pipeline operations being impacted by a ransomware incident in their IT environment, and then operators temporarily halted OT operations as a precaution. Like any pipeline, Dragos would expect Colonial Pipeline to have so many dependencies between their control and SCADA systems into their business systems that it becomes hard to reasonably delineate and separate. With this in mind, out of an abundance of caution, halting operations becomes the safest choice.

Colonial Pipeline is a midstream Oil and Natural Gas (ONG) pipeline and storage company based in Alpharetta, Georgia, USA that transfers refined petroleum products between downstream refining facilities to storage sites and handling transfer from upstream production sites to downstream refining facilities for a large majority of the United States.

This blog is intended to share what is known about the Colonial Pipeline cyber attack, offer a perspective of what subsystems can be found and what operations occur within pipelines to those unfamiliar, and offer recommendations to asset owners based on similar ransomware cases Dragos has worked in OT networks, including from the same group, DarkSide.

DarkSide and Ransomware Outlook

On Sunday, May 9th Dragos released an intel report to our customers that assessed with high confidence that the DarkSide ransomware group was responsible for the IT compromise. During the past year, various manufacturing industries have reported similar incidents and have attributed them to other ransomware groups such as REvil, and CL0P. The recent pattern of ransomware incidents encrypts filesystems and steals either confidential information or Personally Identifiable Information (PII) from the organizations and threatens to post the information on dedicated leak sites (DLS) unless the ransom is paid in a timely manner. During the past year, Dragos has observed several instances of this happening in multiple industrial sectors, including against the major vendor and asset operator, Honeywell. No industry has been immune to this with numerous cases taking place in manufacturing as well as electric power sectors. However, the Colonial Pipeline cyber attack is the most disruptive incident Dragos has witnessed on US energy infrastructure from cyber intrusions.

DarkSide, and many other ransomware groups, are opportunistic. They find soft targets, evaluate if they are a strong candidate to ransom, and then they attack.

Unfortunately, this applies to many industrial companies. These groups rely on weak passwords via unsecured internet exposed services such as Remote Desktop Protocol or exploits against a vulnerable version of common internet-facing devices. Numerous vulnerabilities have been released over the past year for these types of devices to include Pulse Connect Secure, Fortinet FortiOS, and Accellion FTA devices. Once initial access is achieved, they quickly bring in tools focused on gaining Domain Administrator access to enable them to then deliver their ransomware. Dragos response teams have observed this initial access to the deployment of ransomware ranging widely with ransomware delivered as quickly as 24 hours from initial access while in other cases several months before the group deploys their ransomware payload. In our incident response cases and assessments, Dragos often finds shared credential management between IT and OT networks such as connected Domain Controllers as a mechanism to impact OT.

How a Strong Architecture Can Support Response Efforts

Although this attack was carried out on the Enterprise network, it brings to light the highly interconnected nature of OT operations that businesses must consider. Many organizations feel they have highly segmented OT networks to include their industrial control systems (ICS). However, in Dragos’s assessments and cases, we find this to not be the case. It is common to hear about pending IT-OT convergence, but in reality, much of that convergence took place a decade ago, and the preventative controls, such as segmentation, that the organizations had in place have atrophied over time through misconfigurations, additional devices, or just the nature of needing increased connectivity for the business. What the industry is experiencing now is the digital transformation of our infrastructure, which is resulting in hyper-connectivity not only to the corporate IT networks but also personnel, vendors, integrators, original equipment manufacturers, and cloud resources.

Responding to ransomware attacks in the OT environment is even more challenging due to the overall lack of network monitoring and host-and-network based logging. At a minimum, crown jewels, which are the most critical assets in operational systems, should be actively monitored. When preventative measures fail or atrophy over time, asset owners and operators are often at the mercy of discovering the incident only after the malware has executed and run its course, encrypting systems and taking them offline. Unfortunately, during incident response engagements, Dragos has found that many companies have little visibility into the operations and production networks. This slows down incident response and removes options from the company on what they can do to blunt the incident. Those organizations that are proactive and develop consistent insights using frameworks such as the collection management framework are able to know what the most relevant logs are, where they are stored, and how long they are available. These simple types of actions rapidly increase the ability to respond to incidents. Often in incident response cases, almost nothing is available.

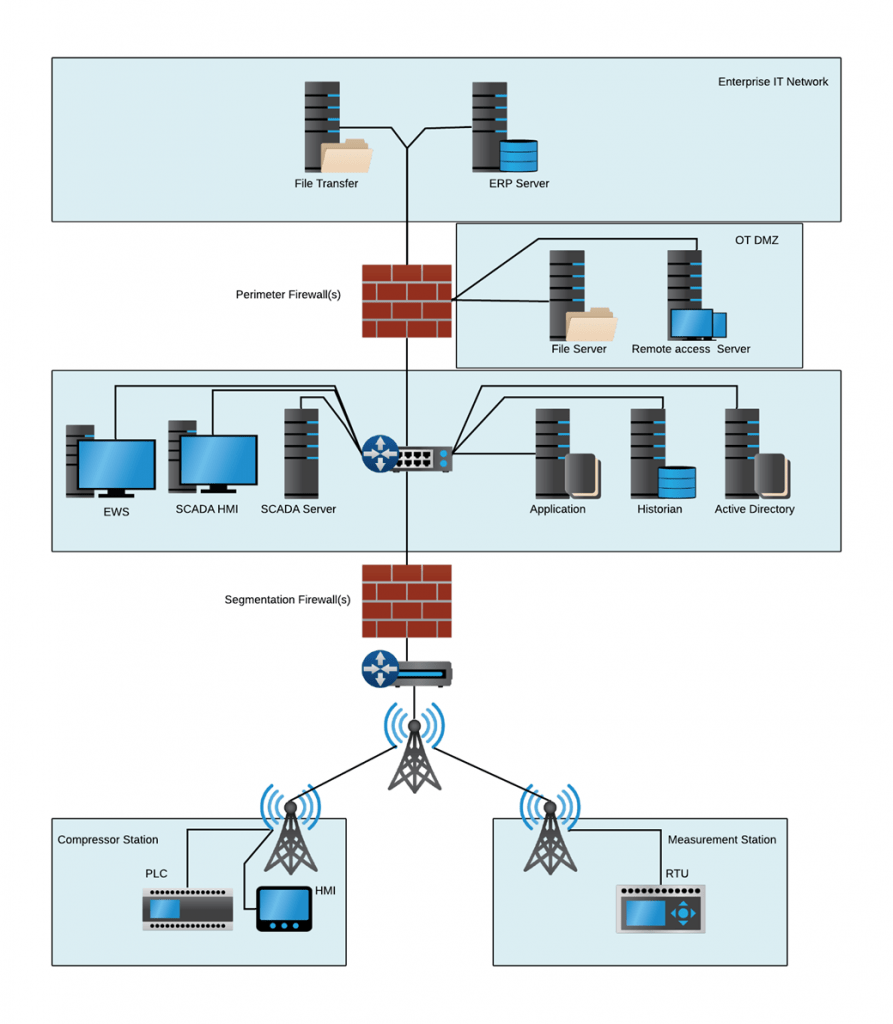

Complete segmentation is often impractical, but a defensible architecture can still be maintained that significantly reduces risk and makes the response more effective. As shown in Figure 1 below, SCADA systems should be architected in such a way as to provide communications segmentation and disconnection points in case of an attack. Limit what protocols communicate through this segmentation, as ransomware groups will use protocols such as remote desktop (RDP), windows file sharing (SMB), and Active Directory authentication (NTLM) to move from one zone into another.

With network monitoring and visibility in place, a defender could view malicious traffic coming into the DMZ and begin changing the environment or disconnecting the systems from the outside world. Next, defenders will want to ensure monitoring is taking place down in the SCADA server to identify changes to outstation communications or at the application server to identify if configurations or modifications are occurring. Project files at the Engineering Workstation (EWS) are also a valued target that needs monitoring, protection, and offline backups as they often contain programs and configurations of the SCADA itself or those of remote PLC and RTU devices.

Continuing this example, if remote polling and operational visualizations systems are compromised, the next isolation point is around the communications out to remote pipeline pump and metering stations. Isolating here ensures local systems are kept operational, and control is still possible. If we made it to this point, remote teams would be activated and sent to the remote locations. This is difficult to achieve in a reduced workforce setting common among highly automated environments. Each of these scenarios needs to be discussed and documented in OT incident response plans and regularly exercised.

Again, this is a best-case response scenario with many fallback options. Many of our responses are instead based on loosely segmented networks or networks with no segmentation at all.

Perspective on Pipelines

Pipelines are critical to the entire energy supply chain, ranging from bringing raw crude oil and other products to refineries and plants to provide final product delivery to end-users and customers. Raw or final product delivery occurs through a complex pipe network from the product source to its destination. Storage capacity for products is limited at refineries and chemical plants. Additionally, distribution terminal tank storage also provides the limited capacity needed for swings in customer demand or short-term outages. However, when a pipeline disruption happens, the cascading effects can be witnessed with operational plants curtailing production as feed tank levels drop and finished product tank levels rise to maximum capacity, ultimately resulting in plants shutting down. Terminals supply tanks are drained of their limited resources and are no longer able to supply customer demand. This effect is ultimately played out with escalating fuel prices or complete fuel outages, disrupting transportation and societal norms.

Pipeline systems comprise pumping stations, storage facilities, supply and delivery stations, custody transfer metering, and a vast array of interconnected piping. These systems span large geographic areas and comprise local control and partial autonomous control at these pumping and valve stations with Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) system to provide remote monitoring and control across the entire pipeline network. Apart from internal operations, pipelines are interconnected to product suppliers’ control systems to begin and end product transfer activities. Plant Distributed Control Systems (DCS) interact with pipeline pump and valve stations to enable or disable product flow and share information of process variables around product flow rates, temperatures, pressures, and product quality measurements.

The interconnectivity does not end with control systems. Pipeline operations depend on external IT systems for issuance and product transfer orders, measurement corrections, and invoicing. Business systems, such as SAP and others, are often highly integrated between pipeline operations to serve the business and financial part of the functions. Product orders flow from these IT systems to the SCADA systems to begin movement and batch operations. Final product transfer data is sent back to the IT systems for product measurement correction, inventory management, invoicing, and historization.

Although these IT and OT systems are independent from a systems standpoint, they are highly dependent on the overall business operations. Therefore, “segment and disconnect OT” may not be a straightforward response approach to ensure OT operations during an incident. The pipeline can still operate without the IT counterpart but is severely impacted when that IT system is taken down from a ransomware event, such as has happened at Colonial Pipeline. With OT digital transformation, connectivity from IT to OT is far more common for most ICS asset owners and operators. Dragos has observed the atrophying of prevention controls from assessments and incident response actions. This, coupled with a lack of visibility and monitoring of assets, affects ICS asset owners and operator’s ability to have an effective response to incidents and not detecting early IT-based warning signs of compromise.

Summary of Recommendations

- Review existing segmentation and preventative controls that may have atrophied over time; achieving ICS network monitoring and visibility will allow consistent validation of the preventive controls and make them more robust. Incorporate network monitoring across the internal OT networks to provide continual visibility into these cross IT/OT connections. Ingress/Egress monitoring is important, but due to the nature of ICS, it is vital to achieve “East-West” traffic analysis.

- Identify shared systems or infrastructure on the IT side that could allow an adversarial group to pivot and deploy Ransomware to the OT side. This includes shared Active Directory between IT/OT or potentially insecure protocols, such as SMB, FTP, RDP, VNC, with direct IT/OT access.

- Review dataflows of critical business system applications reliant on OT communications and document them. This may include historians, SAP, or other Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) systems. Ensure they are understood, risk assessed and included in both the business continuity and disaster recovery plans.

- Engage firms with OT/ICS incident response experience if internal resources are not trained or readily available. Ensure that Incident Response (IR) plans are current, and conduct Table Top Exercises (TTX) to rehearse those plans that include both IT and OT staff.

- Ensure backups are being performed across critical OT systems, such as data historians, SCADA servers, and their databases. This also includes PLC/RTU project files, which may be absent from conventional backup systems. Periodically test the backups and ensure there is an offline copy in the event that an online system becomes encrypted from ransomware.

If you’ve read our recently released Year In Review you’ll find many commonalities- our top 5 recommendations from 2020 all are highly relevant to this activity. Finally, realize your IT and Security staff are usually already under-invested. Picking up a whole new mission set with focus (OT) requires additional resources. Elevate the conversation in your organizations and invest in your people to enable your business.

Securing Remote Access for Pipeline Systems

With SCADA systems, remote operations are just part of “normal operations.” However, remote access into SCADA workstations and servers from enterprise systems or the internet is a significantly different discussion. Simply firewalling off the SCADA is not the right answer. Remote access from untrusted networks into critical OT networks requires needs careful consideration to ensure usability needs and remote workforce requirements are not providing a wide-open path for adversary groups. Dragos has written a blog focusing on secure remote access titled A Matter of Trust: Remote Access for ICS. That blog is still very relevant in light of increased remote operations and engineering requirements of today’s workforce, and the recommendations still apply:

- Engineering and OT teams should evaluate what systems should leverage remote access.

- Remote access requirements should be determined, including what IP addresses, communication types, and processes can be monitored. All others should be disabled by default. Validate your external exposure of IT and OT systems using tools such as Shodan.

- User-initiated access should require multi-factor authentication from the Internet to a DMZ with a dedicated jump host for ICS-specific communications. This system should leverage its own identity and access management system.

- From the DMZ, after authentication, user-initiated remote access should follow a trusted path to the OT system—where the user will authenticate again, this time using the local identity and access management solution.

- All remote access communications should be centrally logged and monitored. Various detection techniques should be implemented on remote access systems, such as looking for brute force attempts or specific exploits for known vulnerabilities.

What’s Next?

All signs point to an opportunistic attack across IT systems, disrupting a significant portion of infrastructure. Our infrastructure is increasingly connected with a growing gap in our visibility to both understand and defend it.

As a community we have a long road ahead of us. Many pointed questions will be asked by media and policymakers over the coming weeks and months. We must focus not just on protecting our infrastructure but also on assuming those protections will fail. And we also must educate our peers, policymakers, and local communities.

Ready to put your insights into action?

Take the next steps and contact our team today.