Spear phishing is one of the most commonly used initial access vectors adversaries leverage to gain a foothold into a network. However, sometimes when we think about phishing, we focus too much on generalist lures and themes not pointed at a specific target. Theming such as fake invoices, third-party supplier masquerading, and impersonation of key business personnel such as C-level executives immediately come to mind. Typically, these campaigns are aimed at a broad recipient group across an organization or industry vertical. However, some recent spear-phishing campaigns have used a more refined approach and specifically have targeted engineering staff or staff involved with critical operations.

If the user clicks on the link in the spear-phished email, and subsequently the malicious payload executes and captures credentials, the adversary may directly access the operational technology (OT) network. Getting access in this way is faster than traditional methods of spear phishing a wide net of victims, getting execution, then pivoting through the informational technology (IT) environment into the OT environment. If they can refine the theming of the phishing lure to be specific to engineering, which may result in a higher click rate, then they can obtain access to machines that have dual access to both the IT and OT networks or the victim’s credentials for both network environments.

Multiple Dragos-tracked threat groups have shown these capabilities.

TALONITE

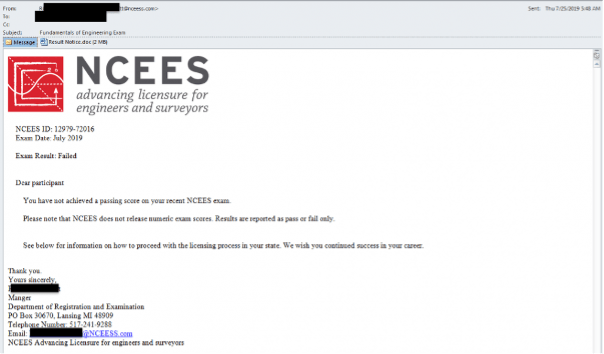

Dragos first began tracking the TALONITE threat group in July 2019 whose operations focused on initial access compromises in the U.S. electric sector. TALONITE uses phishing techniques with either malicious documents or executables. TALONITE uses two custom malware families that both feature multiple components known as LookBack and FlowCloud. TALONITE focuses on subverting and taking advantage of trust with phishing lures focused on engineering-specific themes and concepts. In this specific example, TALONITE masqueraded as the National Council of Examiners for Engineering and Surveying (NCEES) and themed the phishing lure around the failing of an exam related to a license. This specific type of theming may increase the likelihood that engineering personnel may open the attached document containing malware.

Additionally, TALONITE also sent phishing emails masquerading as the North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC), Global Energy Certification (GEC), and American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE).

ALLANITE

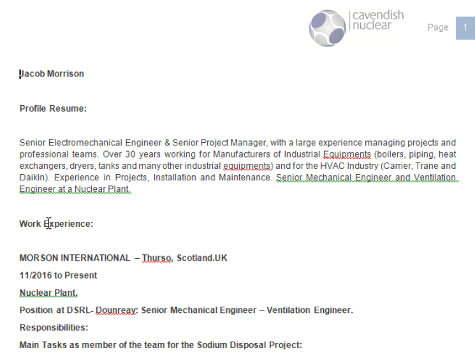

ALLANITE accesses business and industrial control (ICS) networks, conducts reconnaissance, and gathers intelligence in the U.S. and United Kingdom electric utility sectors. ALLANITE uses email phishing campaigns and compromised websites called watering holes to steal credentials and access target networks, including collecting and distributing screenshots of industrial control systems. In a 2017 campaign, ALLANITE sent documents masquerading as engineering resumes to industrial infrastructure companies. In this case, the intended victims could have included corporate staff such as human resources; however, it is expected that personnel with an engineering background could also be reviewing the resumes to assess a candidate’s suitability for a role.

STIBNITE

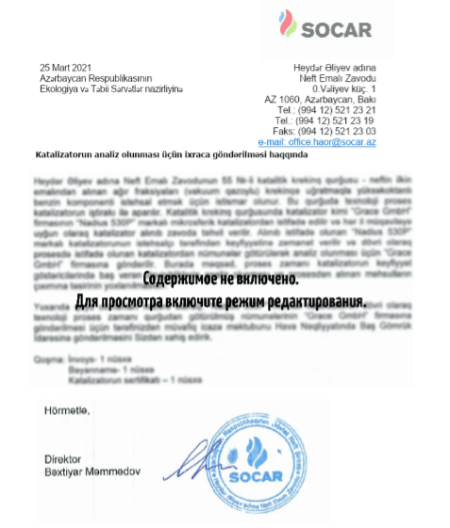

STIBNITE targeted wind generation organizations and government entities in Azerbaijan from late 2019 through 2021. In one campaign, STIBNITE utilized phishing lures masquerading as the State Oil Company of the Azerbaijan Republic (SOCAR). The heading of the attached document translates from Azerbaijani to English as “Concerning export for catalyst analysis.” The remainder of the document appears to present a letterhead and signature block to make it appear legitimate; however, the email address listed is incorrect. Additionally, the bolded text over the blurry paragraph translates to “Content not included. To view, enable edit mode,” which, if the direction wallowed the directions followed by the recipient, would allow the malicious macro to execute.

Follow On Activity – Watering Holes

Adversaries can use many different techniques to conduct the next stage of their attack after successfully gaining initial access through spear phishing. Two examples include delivering malicious documents with embedded payloads, or credential harvesting from a login page masquerading as a legitimate authentication service. Sophisticated adversaries can also compromise legitimate websites and use them as a “watering hole.” A watering hole refers to a a compromised website that is likely to attract visitors from an intended victim or group of victims. The adversary can modify the web pages to capture credentials, distribute malware, and track user activity. An adversary can also configure the website so that the malicious activities are only executed against visitors who come from a site from a specific IP range. This could, in turn, aid the adversary in evading detection from the legitimate site owner, possibly for an extended period of time.

One example occurred in 2020 when DYMALLOY compromised various Ukrainian industrial supply providers and placed malicious code in a Java script on their sites. This script was used for credential harvesting through generating a server message block (SMB) connection to the victim host and then collecting the user’s New Technology LAN Manager (NTLM) hash. This enabled DYMALLOY to bypass the victim’s firewall and infect the victim’s network, collecting the credentials for use later.

Follow On Activity – Spoofed Services or Organizations

In addition to watering holes, an adversary can also register domain names that attempt to masquerade as trusted services or organizations. This can be achieved through “typo-squatting” where a domain name is registered with a small number of incorrect characters in the name, potentially picking up unsuspecting victims who might type in the legitimate domain incorrectly. The adversary can then mirror the content of the legitimate site, albeit with additional nefarious code. These domains can also be used as Command and Control (C2) servers so that defenders will deem them legitimate when reviewing security logs.

Another variation on this technique is the use of “Punycode.” Punycode is the representation of Unicode with the ASCII character subset that is used for domain names. Adversaries employ this technique by using an internationalized domain name (IDN) homoglyph. Basically, adversaries register domains using the IDN capability, substituting English letters with Cyrillic, Greek, and other characters that look like English letters. For example, the domain “dragos.com” versus “drαgos.com”. In this example, the ‘a’ in Dragos is substituted with the Greek character for alpha. In IDN notation, the domain would be registered as xn--drgos-e9d[.]com. Such an extended IDN domain is noticeable in web traffic logs; however, a client browser will render it to show as ‘drαgos[.]com’ which can deceive the user into thinking they are browsing a legitimate website.

Mitigating Against Spear Phishing Attempts

Dragos recommends the following mitigations for engineering-themed spear phishing:

- Conduct targeted phishing simulations against engineering staff that utilize engineering-themed lures.

- Educate engineering staff on the dangers of specifically targeted spear phishing campaigns.

- Make a list of common engineering regulatory and licensing bodies in your country and industry vertical. Review the mail flow metadata of any suspected communications with the organizations and try to find anomalies. Additionally, look for evidence of further communication through other mediums with these bodies that may not be legitimate in a scoped and planned threat hunting exercise.

- Review areas where operations staff have access to the internet or email utilities from machines that also have access to OT environments. Rethink whether these areas should have access to both IT and OT networks and find other solutions for operations staff to access the internet away from machines with OT network access.

- Consult with your operations and engineering teams on whether they have seen any emails fitting these themes. There may be instances where phishing emails have made it through all layers of protection and have already arrived at the end user.

The following steps can prevent credential theft from watering holes (similar to the DYMALLOY activity):

- Block outbound SMB (port 445) and NetBIOS (port 139) at the firewall. Monitor for attempted SMB/NTLM credential harvesting attempts. Failed requests often have the PROPFIND, then OPTIONS HTTP methods with a WebDAV User Agent. Requests to adversary infrastructure will always utilize an IP address as the address with no corresponding DNS lookup.

Dragos recommends the following in relation to spoofed services or organizations:

- If you are a Dragos Worldview customer, be aware of the weekly Suspect Domains Report. This report contains newly registered domains that could be trying to masquerade as known ICS and IT brands in an effort to deceive unsuspecting users.

- To discover the use of Punycode, conduct threat hunting activities against your web, network, and proxy logs to identify traffic to domains that contain the ‘xn--’ string. You will uncover legitimate traffic to international websites that use languages other than English in their domain name; however, baseline what is normal and what warrants further investigation. Excessive data transfer outbound, consistent timing of network intervals, and strange user-agent strings are indicators of activity that should warrant further investigation.

Ready to put your insights into action?

Take the next steps and contact our team today.